Hollywood wants Jonathan Taylor Thomas, teen idoldom’s beau ideal, to be the next Macaulay Culkin. He’d prefer to be the next Ron Howard

Head down, fingers interlaced as if in prayer, thirteen-year-old Jonathan Taylor Thomas is sitting in the rough-hewn witness dock of Tom and Huck‘s faux 19th-century courtroom, silent and still for what seems like the first time in days. Just moments before, he was joking and backslapping as he entered the Mooresville brick church, fresh from watching the NBA playoffs near the soundman’s setup. But if there is a key dramatic scene in the Walt Disney Company’s latest cinematic retelling of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, then this is it: the moment when Tom breaks his vow to Huckleberry Finn and declares that the man accused of Doc Robinson’s murder— amiable widebody Muff Potter—is, in fact, innocent. “Give the actor some help,” yells first AD Howard Ellis, the set’s alpha male, and, as if on cue, Tom & Huck’s unprepossessing British director, Peter Hewitt, ambles over to Thomas, leans into him with an almost paternal mien, and calmly starts discussing the scene.

Hewitt’s initial reaction to the casting of Thomas was less than enthusiastic. Though he’d never sat down to watch an episode of Home Improvement, Hewitt feared that a veteran sitcom child would be too cool, too laid-back, too hipper-than-thou for the grittiness he wanted to bring to the Tom Sawyer saga. Thomas’s initial readings allayed his concerns, and, after a week or so of dailies, Hewitt sussed out that Thomas’s pretake joshing was actually a part of his technique.

Now, however, a subdued Thomas needs a little guidance from his director. And so Hewitt instructs his star to keep one emotion uppermost in his mind: “This is your time to stand up and say. Fuck off—I was there, I saw it, all of you just fuck off.’ ”

Well, whatever. Hewitt’s counsel works: On “Action,” Thomas leaps out of his chair, slams the side of his hand onto the courthouse Bible, and delivers a well-modulated, full-intensity blurt that will set the stage for the rest of the film’s derring-do. It’s a performance forceful enough to warrant the considerable coverage Hewitt wants to give it . . . but as the late-May swelter of this Saturday in Alabama finally begins to abate, there are indications near the back of the courtroom of what some shows like to call kinderpanic.

By law, underage actors are only allowed to work a given number of hours a day; throughout the shoot, scenes have been rewritten and shot selection recrafted to maximize Thomas’s on-set time within Tom & Huck’s $10 million budget. There are less than fifteen minutes left on Thomas’s clock today, and so while lighting setups are being frantically changed, a spirited discussion takes place among Ellis, Hewitt, and executive producer Barry Bernardi. “You see no panic,” Bernardi tells a visitor, “but my sphincter is going . . .”

The only member of the production team who seems wholly unpuckered is Thomas. Earlier that day, he needed an ice bag, some balm, and an Advil after a window slammed down on his elbow during second-unit shooting, but now he’s alert and raring to go. Knocking out lines and quick reaction shots with professional aplomb, Thomas does his part to keep things on schedule. Before being sent off the set at his witching hour, Thomas finally flubs a take: “Are you hot?” he quips to no one in particular. “I’m very hot.”

If you don’t know how right he is, you haven’t been paying attention. For the past five years, Thomas has starred in the top-ranked ABC sitcom Home Improvement. That gig, combined with his performance as the (nonsinging) voice of Young Simba in The Lion King, made Thomas a teen idol who now receives an estimated 50,000 pieces of mail per month. In the process he has joined such esteemed ‘throbs of the past as the Monkees, Rick Springfield, and New Kids on the Block as a cover boy for a raft of preadolescent magazines like Bop and 16, which each month chronicle the likes, dislikes, semiromantic reveries, and celebutante appearances of the boy they call JTT.

Hollywood’s wake-up call came early last year, with the astonishing $9.5 million opening weekend of Thomas’s first live-action feature, Man of the House. (Since costar Chevy Chase’s previous movie had opened at $3.7 million, the industry had a pretty good idea of who the public was paying to see.) Now, with Tom & Huck trailers set to be stuck onto Toy Story and an overall commercial buy estimated at more than twice the film’s budget, Disney is giving Tom & Huck the kind of full-on star sell usually reserved for Tom Cruise vehicles. If Tom & Huck performs up to par, Thomas, who turned fourteen last September, will become the first bankable young actor since Macaulay Culkin.

For a child-star industry that grew fat on family TV shows, only to witness the rise of the hour-long adult drama—and that has seen its big-screen mainstays wind up in the tabloids, in rehab, or in retirement— Thomas’s ascent can’t come soon enough. Michael Kinsley once described Albert Gore as “an old person’s idea of what a young person should be,” so figure Jonathan Taylor Thomas for the Al Gore of teen idoldom: intelligent, funny, mature, loaded with craft, and watched over by a mother seemingly more intent on the development of his brain and heart than his bank account.

Rick Rodgers, Bop’s elfin editor, wonders whether there’s a 40-year-old man hiding somewhere beneath Thomas’s tawny skin. It’s an observation that is made a lot, and not just because Thomas is worldly beyond his years. You can hear it in his voice: It’s slower, almost a drawl, and less eager to impress than that of other bright kids. He plays street hockey, but his love is fly-fishing, and he has the wistful detachment anglers often have.

“It’s odd that as soon as a film opens, people become interested in you,” he says one day in his trailer, between scene changes and his on-the-set schooling. “It’s great that we’re getting scripts, but why? Is it because you can act, or because your film opened well? It’s confusing, especially for a kid.”

All too true: Consider the case of the Walt Disney gift. In the wake of of the House’s phenomenal opening, a token of congratulation was clearly in order. So the Disney bigwigs asked. What does Jonathan like? The answer was, of course, fishing—so the Disney people procured a top-of-the-line fly rod, and dispatched it to Thomas that Monday with the studio’s heartiest thanks for a job well done.

But that Monday, like most Mondays, brought Thomas to Home Improvement alongside Tim Allen, who just a few months earlier had made his motion picture debut for Disney. Allen’s The Santa Clause had enjoyed an equally impressive opening, and the Disney people had sought to reward him as well. They’d gotten Allen a Porsche.

Thomas’s agent, Tracy Brennan of ICM, promptly brought to Disney’s attention the disparity in the stars’ swag. Later that day, a large package was delivered to Thomas. Inside was a full-throttle home-entertainment center that apparently looked like something out of a Matt Helm movie.

So which is the lesser evil: the inability of studios to recognize that their minors are every bit as hardworking and worthy of their largesse . . . or that the very greed and ingratitude for which we would scold a child we encourage in a talent agency acting on that child’s behalf? Yes, it does get confusing, especially for a kid like Thomas. No wonder he seeks civilians for his private-time companions.

“You can’t be trapped in this bubble called the acting industry,” he says. “The industry is neurotic and weird, and so when I go home and I play basketball with my friends. I’m not Jonathan Taylor Thomas. I’m just Jonathan. I don’t like hanging out with other actors and actresses.” Too sane to be a poet, too levelheaded for glamorous rebellion, Thomas is building a career that provides a promontory from which to observe the death valley that young stardom has lately tended to become— a prime example of which lies no farther away than the neighboring Tom Huck trailer.

I’d like to direct and I think I’ll have the chance. I’m only thirteen: I can learn a lot between now and when I’m actually old enough to be in the DGA.

During his audition for the role of Huck Finn, twelve-year-old Brad Renfro grabbed an ax and chased a casting assistant around the office—because, he said, “if I couldn’t have her, then nobody could.” He and his electric guitar stay out well into the wee, wee hours playing “Anarchy in the U.K.” at a club in Huntsville. The Tom & Huck producers are paying an “acting coach” $10,000 a month to keep him in line, but neither she nor anyone else can stop the packs of cigarettes, or the girls in his trailer.

Of course, even he knows just how big Jonathan Taylor Thomas is: At Hooters, Renfro told the bouncers, “I’m the kid with the kid from Home Improvement.”

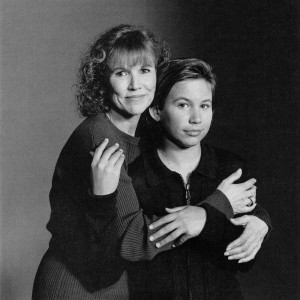

The kid from Home Improvement was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, second son to Stephen and Claudine Weiss. In 1986 the family moved to Sacramento, where Jonathan did some print modeling and the occasional stage show. He was still calling himself Jonathan Weiss the first time he met casting director Deborah Barylski, who was auditioning youngsters for a made-for-TV movie called Quess Who’s Coming for Christmas. He didn’t get the role, but she liked what she’d seen—so in 1991, when it came time to audition boys for a highly touted sitcom pilot entitled Home Improvement, Barylski thought of Weiss, who was by now calling himself Jonathan Taylor Thomas, perhaps because his parents had split up. Barylski’s March 20, 1991, notation next to Thomas’s name reads: t.o.d—in other words. Test Option Deal right away.

Some seventeen executives crowded the room for Thomas’s audition. After it was done, Richard Frank, then head of Disney television, made the kind of remark that’s only recalled when it’s so prescient: “That kid’s gonna be a star.”

But it didn’t really happen—at least, not right away. When the show hit number one, it did so, in the eyes of the industry, on the strength of Allen and his stand-up skills. Thomas, along with colleagues Zachery Ty Bryan and Taran Smith, were “the boys.” By the beginning of the third season, in 1993, that had begun to grate a bit.

So on the third season’s first day of shooting, the boys called in sick. Press reports said they were asking for a salary increase from $8,000 to $25,000 per show. Bonnie Ventis, Thomas’s original agent, asserts that “creature comforts” were a greater issue: The boys’ onset chairs were chained together, she says, and they could only play basketball in a truck lane.

Perhaps. Disney wasted no time in responding to the sick out: It reopened auditions for the roles. “Disney’s feeling was, no one’s going to hold up the show,” says executive producer Carmen Finestra. The boys returned the next day. It may have been a PR debacle for the young actors, but that season saw Thomas’s star begin to rise; says Finestra, “That’s when I started to hear, ‘Boy, that middle kid, I like him.’ ”

But even while Disney’s TV side was playing hardball, the feature-animation folks had chosen him over dozens of boys to play The Lion King’s Young Simba. Codirector Roger Allers recalls holding the now four-foot-eleven Thomas upside down and shaking him for audio verite during the wildebeest stampede. More poignantly, Allers also recalls the psych job he did on Thomas to gear him up for Simba’s discovery of his dead father. “We were talking about how it would feel if he had lost his parent,” recalls Allers. “Since his mother was always there, and I knew they must be close, I used her as an example: ‘Think of how this would feel: You’ve just seen your mother fall into a river and now you’ve found her washed up.’ ” Simba’s first line in the scene is an anguished cry of “Dad!” “But after I coached him into thinking through it that way,” says Allers, “we said, ‘Let’s go,’ dimmed the lights… and Jonathan said, ‘Mom!’ ”

In the fall of 1994, on the heels of The Lion King’s success, Claudine left Ventis for ICM’s Brennan, who got Disney to pony up an additional $350,000 on top of the $250,000 option it held on Thomas’s next movie, Tom & Huck. With Pinocchio to follow for the ill-fated Savoy Pictures, Thomas is unavailable for film work now until summertime 1996, but that hasn’t stopped the cascade of requests for personal appearances and endorsements. “Jonathan,” says Brennan, “could be his own business.”

Back in his Mooresville trailer, it’s as if Thomas can see the show business landscape littered with the young actors who couldn’t adjust to the distinctly uncute real world. “You know, how serious do you take this stuff? I mean, you should be focused on doing a good job, but—it’s a And every job has an end. I think most of those children weren’t prepared for the end. I mean, it’s not the end of your life! You can’t base your life around one thing. So that’s why I focus on school, I play sports, I learn the technical side of [filmmaking]. Because sometime it’ll change, and I’ll have my education to fall back on.”

Indeed, Thomas seems eager for that day to come. As he envisions his future, it looks a lot less like Mac Culkin’s and a lot more like Jodie Foster’s or Ron Howard’s. Thomas wants to go to college – he’s already visited Yale, Harvard, and NYU – and then “I’d like to direct, I really would. And I think I’ll have the chance, you know? Being able to see this firsthand is the best experience you can have, unless you’re the son of Steven Spielberg. I’m only thirteen: I can learn a lot between now and” – he laughs – “when I’m actually old enough to be in the DGA.”

Until then, though, Jonathan Taylor Thomas is still a boy, and it might have been a reflection of the crew’s respect for him, their acknowledgement of his incipient manhood, that they fondly recalled those moments when he acted very much his age. Like the day they shot Tom and Becky Thatcher’s kiss. “Oh man, he really didn’t want to do it,” recalls Peter Hewitt. “He wanted to know how many times, and from how many angles. It was quite cute. I think it was his first screen kiss.” He should be so lucky, right? “That’s what I was saying to him: ‘Look—she’s gorgeous.’ ” “The crew members were reliving their first kiss,” says a laughing Rachael Leigh Cook, who, at fifteen, is a slightly more worldly Becky. “Jonathan was a little nervous.” During one close-up, she says, “we were, like, ‘Nice, Peter—what do you call this, the nosecam?’ ”

Et tu, Jonathan? “I could not believe how many angles Peter wanted,” says Thomas. “When it was getting up into the thirties in takes, I was, ‘You know, my lips are going to fall off pretty soon.’

“But if I wasn’t having a good time doing this, I would not do it. Why would I fall off bridges, and, you know, have to kiss girls if I wasn’t having a blast?” For now at least, the DGA can wait.

Christopher Connelly is an executive editor of Premiere.

Source: Premiere Magazine, January 1996, Vol. 9, No.5 Author: Christopher Connelly Date: January 1996

16 thoughts on “Boy Wonder”