Once upon a time there was —

A king! my little readers will say at once.

No, boys and girls. You are wrong. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood…

Le aventure di Pinocchio

Storia di un burattino

Carlo Collodi

The father of Pinocchio was Carlo Collodi, a disillusioned veteran of Giuseppe Garibaldi’s revolutionary army. When Collodi returned to his native Tuscany in 1861, he found that the Revolution had left Italy in the hands of a corrupt ruling class which offered him and his former comrades little more freedom than the usurping Austrians had formerly provided.

His criticisms of the new regime in “The Streetlight” and “Controversy,” two newspapers he founded, received an icy reception. It was not until his mature years that he turned to writing exclusively for children, at the age of fifty, he translated Pierre Perrault’s Contes de la Mere Oye (Mother Goose Tales) into Italian.

He then went on to tackle his own material. The success of Collodi’s original story Giannetino (Little Johnnie) led to a series of Little Johnnie books which were filled with lessons for children while slyly propagating the author’s political views under the guise of an entertaining tale.

Then in 1881, the editor of a new children’s magazine invited Collodi to submit a story to the first issue of his Giornale di Bambini (The Children’s Newspaper). Originally titled Tale of a Puppet, the series was an immediate hit and ran to 35 installments, before Collodi’s textbook publisher brought it out in book form in 1883 under the title The Adventure of Pinocchio.

For Italian children’s literature, The Adventure of Pinocchio marked a turn away from the kind of overt preachiness Collodi himself had practiced in the Little Johnnie books. The hero of those stories is a real little boy, as capable of selfish mischief-making as he is of feelings of devotion and contrition.

Pinocchio was immediately embraced by an adoring public who found a restless puppet easier to accept than a character that might remind them of their own flawed children.

Actually, the book hit close to home for many parents because Pinocchio brought new realism to children’s literature. Most fairy-tales take place in a world of great castles, beautiful princesses and noble lords and ladies, but this was not a world which fired Collodi’s imagination. Instead he set Pinocchio’s adventures in the real Italy of the common people, teeming with satirically conceived and vividly described social types. As a result, the story became, in the words of one critic, a novel for children inspired by the author’s attempt to recapture his own childhood.

With The Adventures of Pinocchio, and almost by accident, Collodi had finally won the fame that eluded him as a political journalist.

But when The Adventure of Pinocchio began to be translated and adapted in America, it was subjected to the same treatment that befell Mark Twain’s famed Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The story was watered down, and the adapters eliminated the more antisocial tendencies from the character of Pinocchio, whom Collodi had modeled on Punchinello, the Commedia del Arte’s resident anarchist.

Also banished was the extraordinary company of human and animal creatures that Collodi had designed to convey the social and political ills of post-revolutionary Italy. The effect of the censorship is obvious. Pinocchio’s name has become synonymous with the kind of goody two-shoes wholesomeness which Carlo Collodi tried desperately to remove from children’s literature. The original attraction to and reasons for the perennial popularity of his masterpiece have been all but forgotten.

Not that The Adventure of Pinocchio is a tale too harsh for children. Quite the contrary. It’s a revered work of fiction. But it was the Pinocchio-as-protagonist aspect of this classic that captured the attention of the producers of The Adventures of Pinocchio.

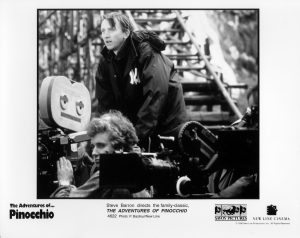

Intrigued by the story and not the myth which has been widely associated with Pinocchio, they turned to Collodi’s source material for their inspiration. “Our film is very much in the spirit of Collodi’s book,” says writer-director Steve Barron. “It’s a wonderful story which people have never really seen on the screen before.”

Barron was introduced to the project by producers Donald Kushner and Peter Locke after they encouraged him to pursue the idea of telling the true story of Pinocchio. Barron, who suggested telling the story with an animatronic puppet, already had considerable experience with animatronics when he made Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and he was a great fan of Collodi’s book.

“The essence of the story is a moral tale,” says the director. “You see the birth of a boy who is going to grow to the age of twelve during the course of the film, even though his physical appearance stays the same. Over a very short period of time, he learns the morals that all boys and girls grapple with and discover during their innocent, formative years.”

“It is also the fish-out-of-water story of a misfit – somebody who isn’t the same as everyone else, but is resilient and strong enough to prevail. People try to rob him and use him and tread on him and burn him…and he is able to overcome all that.”

Barron had one choice for the role of Pinocchio’s creator, Geppetto: Academy Award- winner Martin Landau (Ed Wood), who was delighted to accept.

“It’s a great, classic story,” explains Landau. “In the theatre, we love to play Hamlet or Lear. American actors usually don’t get the opportunity to do that, so the closest one gets is to play something like this…which is a bonafide classic.”

“Our film is very faithful to Collodi’s book, which I have loved since childhood. When I read the sqript, I was moved by it. Steve Barron has fleshed out Geppetto and made him a very interesting character,” he explained.

“He’s a guy who’s very set in his ways, who’s not a very social creature, who has suffered from unrequited love. As a result, Geppetto is somewhat a loner, and he creates his own fantastic world with his marionettes and the figures he carves out of wood.”

“Then because of a phenomenal series of events – carving the heart in the tree, that very piece turning into Pinocchio, that very heart ultimately beating – Geppetto’s hidden feelings show themselves. He winds up having the wife and family he would never have got had he not touched those nerves within himself and rediscovered his way.”

The filmmakers also wanted Jonathan Taylor Thomas to be the voice of Pinocchio and the living Pinocchio at the end of the film. The popular young actor was able to fit in the role between finishing Tom and Huck and starting the new season of his #1 rated television series “Home Improvement.”

“When Pinocchio comes to life as a puppet he is very young,” says Thomas. “He’s just entering the real world, seeing things he’s never seen before, and he’s in awe of everything. He grows and matures throughout the film, so that when he turns into a real boy, he’s got the maturity of a young man.”

Thomas, too, was impressed with Barron’s adaptation of the classic tale. “I think the Collodi book has more of a journey, with exploration and adventures than the versions I grew up on.”

German actor Udo Kier (Ace Ventura: Pet Detective) plays the evil impresario who covets the magical marionette. “He’s got an amazing face, incredible eyes and a real presence,” says Steve Barron.

“In the original story there are three separate villains,” explains Kier, “the puppetmaster who owns the theatre, the man who turns the children into donkeys, and the big monster at the end. For our film, I am a mixture of all three.” (Interestingly, the name Barron picked for his composite villain – Lorenzini – is the real name of the author of Pinocchio. who took the pen-name Collodi from the name of his mother’s native village.)

Like everything else about the production, the strong supporting cast had a distinctly international flavor. Canadian actress Genevieve Bujold (Dead Ringers, The Modems) plays Leona, and “Cheers'” Bebe Neuwirth is paired with “Saturday Night Live’s” Rob Schneider as Felinet and her oafish cohort, Volpe. Corey Carrier (Nixon) plays young Lampwick, Marcello Magni is the baker, and the British comedienne Dawn French is the baker’s wife.

Among the first technicians brought on board after Steve Barron was attached were production designer Allan Cameron and cinematographer Juan Ruiz Anchia, who had just collaborated on the live-action Jungle Book. Anchia’s stylized lighting of day and night scenes would contribute greatly to the dream-like atmosphere of the film.

Barron and Cameron chose as their principal location the 15th Century Czech town of Cesky Krumlov, located two-and-a-half hours south of Prague. “A lot of dressing and repainting of buildings was required,” says Cameron. “Putting on shutters, taking down TV aerials, removing all the paraphernalia of a modern town and replacing it with the look and feel of the past.”

“The date of the film is fairly nebulous – it goes from about 1790 to 1860. That’s so we could get the best look in everything…costumes, hair-styles, architecture. We really went for a romantic look.”

Maurizio Millenotti, twice nominated for Academy Awards for his work on Franco Zefferelli’s Othello and Hamlet, designed the actors’ wardrobe, make-up and hair.

“The look of the film is fantastic,” comments Bebe Neuwirth. “It’s really like illustrations from a book of fairy tales. Maurizio’s make-up and costumes for Felinet helped me discover my character – although actually, I have played lots of catty characters before.”

“The most interesting set to design was Terra Magica,” says Allan Cameron, “a trap where bad boys are turned into donkeys. It was fascinating to build because it’s supposed to be pieced together rather crudely, but still have the ability to attract the boys. It was erected over four acres — a huge set, but the valley it’s in is even bigger.”

Other Czech locations included the interior of a courtroom at Schloss Troya, where 300 costumed local extras were employed; the village clock tower at Trebiz; the monastery at Klotovy; the high sea road and waterfall at Lorn Chlum; the pine forest at Yojtechov- Mseno; and, in Prague itself, the exterior of a classroom at Jansky Vresk and the courtyard at the French Embassy.

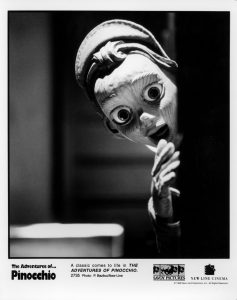

After twelve weeks of filming in the Czech Republic, the production moved to the Jim Henson Creature Shop in London to complete the visual effects and process work necessary to bring the film’s magical hero to life.

The Creature Shop wizards supplied not only the film’s star, but an eight-foot sea monster, donkey prosthetics for the transformation sequence in Terra Magica and prosthetic make-up for Udo Kier to wear when Lorenzini begins his transformation into the whalish sea monster.